How the descendants of slave traders and the descendants of the enslaved now meet on the same soil — to remember, reconcile, and reclaim.

(c) Remo Kurka / Slave Vessel (as it was)

In 2019, Ghana launched the "Year of Return", inviting Africans in the diaspora — especially African Americans — to "return home" and reconnect with their ancestral roots. The initiative was widely celebrated as a groundbreaking effort in heritage tourism, historical healing, and Pan-African solidarity.

But beneath the emotional ceremonies, cultural performances, and tears shed at the "Door of No Return," a deeper and more complex story lingers:

Many of the coastal Ghanaian communities now welcoming these descendants of the enslaved were directly involved in the transatlantic slave trade.

This creates an undeniable historical irony — one that demands reflection, not shame. It’s an irony that reveals the complex legacy of slavery, the complicity of African elites, and the transformative power of historical reckoning.

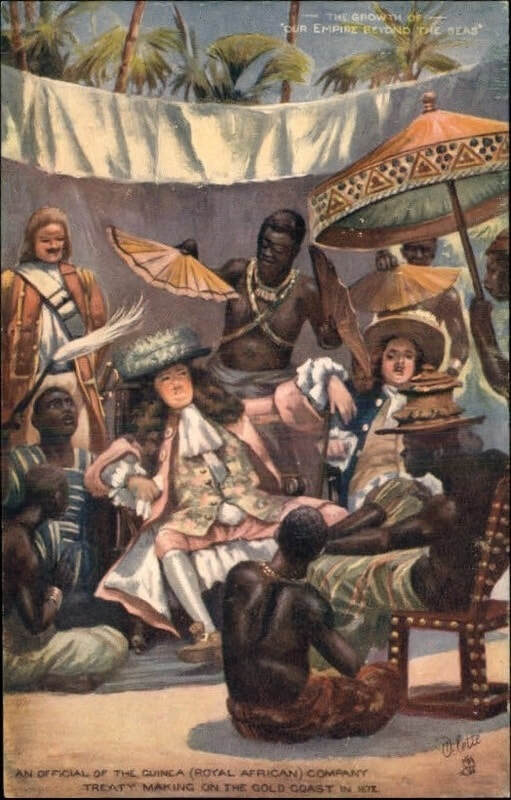

Between the 1500s and 1800s, the Gold Coast (modern-day Ghana) was one of the most active hubs of the transatlantic slave trade. Forts such as Cape Coast Castle, Elmina Castle, Fort William (Anomabo), and others served as processing and shipping points for millions of enslaved Africans.

Contrary to a simplified narrative of Europeans raiding villages alone, the trade was heavily dependent on African collaborators, especially from coastal tribes like the:

Fante

Ga

Nzema

Ahanta

Anlo Ewe

Akyem and Denkyira (inland supply networks)

These groups often served as intermediaries, war captains, or political elites who captured or purchased people from the interior and sold them to European traders.

Their motivations were varied:

Access to European goods (guns, alcohol, cloth)

Political leverage over rivals

Economic prosperity in a shifting colonial world

Fast-forward to today, and many of these same communities are the ones welcoming the African diaspora back — not as captives, but as honored guests.

In Anomabo, where Fort William once exported more slaves than Cape Coast Castle, descendants of slave traders now lead cultural reconnection ceremonies.

In Elmina and Cape Coast, locals perform symbolic "return rituals" to honor those lost.

In Accra, the Ga community, once linked to European trade networks, now hosts diaspora naming ceremonies and community reintegration events.

The descendants of those once sold are now met with apologies, drumming, libation, and embraces.

Yes, it’s ironic. But it’s also beautiful.

This irony should not be ignored — but neither should it be oversimplified.

Not all Africans were complicit. Many were victims of war, betrayal, or circumstance, including from the very coastal communities that profited.

Some local leaders resisted the slave trade, while others were coerced by colonial powers or rival kingdoms.

The European demand for slaves, and the military power of European guns, created a system that many Africans could not resist, and some exploited.

The history is complicated, painful, and shared.

What the “Year of Return” and its ongoing legacy (“Beyond the Return,” Panafest, etc.) have created is a moment of historical return and reckoning:

Descendants of slave sellers and slave buyers now stand side-by-side, confronting a common history.

The soil that once bore the chains now hosts healing ceremonies, truth-telling, and calls for global unity.

Spiritual reconciliation is replacing historical silence.

This is not just irony — it's transformation.

The fact that descendants of those who profited from the slave trade are now at the forefront of remembrance, welcome, and healing speaks to something greater:

A willingness to acknowledge history, not bury it

A desire to make peace with the past, rather than deny it

A belief that shared ancestry, even when painful, can be a source of unity, not division

Ghana has become the symbolic and spiritual ground zero for the diaspora’s reconnection with Africa. Not because its history is perfect — but because it is honest enough to face it.

The descendants of both captors and captives now come together not as enemies, but as fellow inheritors of a complicated past — and as partners in building a more conscious future.

So yes — there is irony.

But there is also power.

There is grace.

And there is a chance for a new story to begin — one not of chains, but of reconnection, respect, and restoration.

Advertisement