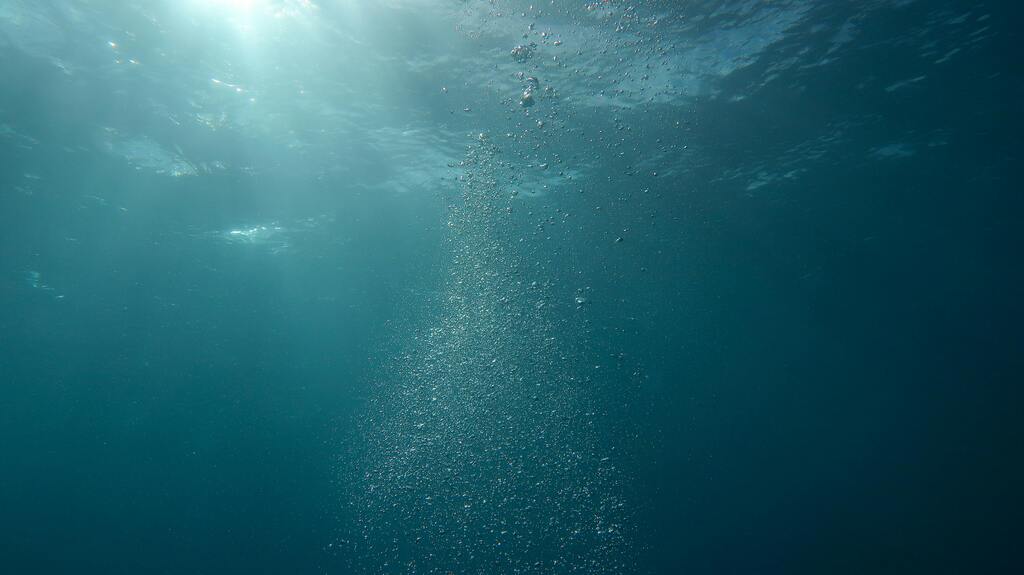

(c) Remo Kurka / Sailing vessel, used for slave trade. Inside the hold. (Example photo)

They say the wind changes when a nation’s conscience shifts. But wind is wind, and profit is profit. I have lived long enough to see Amsterdam make gold from blood, and then pretend to forget where it came from.

When the Company received orders from the Hague—“End the slave trade”—they meant only the public kind. They closed the books, but not the ports. The governor still nods when I walk past. The harbor still fills with canoes at night. The Africans still bring captives from inland. So we still load them—only now, without uniforms, without reports, and without glory.

This is the new era of trade: quiet, hidden, shameful. But no less lucrative.

The ship is called De Vlinder—The Butterfly. A cruel name for what she carries.

Tonight, we load forty-seven souls. Women, children, a few young men too broken to resist. They come through the west gate under moonlight, no drums, no torches. Just shuffling feet on damp stone. There is no priest to bless the journey. Only my signature on the ship’s false manifest: “Cargo – palm oil and ivory.”

God forgive us. Or don’t.

I no longer pray.

Find your roots and rise — Ghana3d.com Gateway Experience 360 is your ultimate guide to cultural, historic, and soul-stirring adventures. Whether you're returning to your ancestral land or exploring Ghana for the first time, we offer curated journeys that connect you deeply to the spirit of West Africa. From powerful walks through Cape Coast & Elmina slave castles to the vibrant rhythms of Accra’s nightlife. From sacred village ceremonies to awe-inspiring natural beauty — your journey starts here.

Photography (c) Remo Kurka

My father was a warrior. He said never trust a man who wears silk in the sun. Yet I stand here, sword at my side, guarding white men and their stolen cargo.

They pay in coin, cloth, and powder. They say we are partners. But partners don’t keep secrets and change flags.

I was told the Dutch had stopped selling people. That Holland had found its soul. Yet here we are, at the lower courtyard, near the mouth of the Male Dungeon, loading captives through the coastal tunnel, just as my grandfather once did.

But it is different now. There is no honor. No celebration. No justification. Even the chiefs bring fewer people. They whisper that Europe now punishes what it once praised. That the white men are hunted by their own navies. That these may be the last ships.

I watch the girl with the shaved head. She does not cry. She does not look away. She walks barefoot past me into the hold like someone who has already died.

I cannot meet her eyes.

Advertisement

I have not spoken in three days. My tongue is cracked. My wrists are raw. My eyes are dry.

They took me from my village at dawn. My brothers are dead. My mother’s wailing still echoes in my skull.

They marched us for days. Gave us nothing but dirty water and words I didn’t understand. They pushed us into a stone room that smelled of piss and iron. I do not know how long I was there. Only that the floor was cold and the sea was near.

Now they put us in the belly of a ship. The wood is wet. The air is thick. We are packed like millet in a gourd.

A man cries out. Another is silent. A baby no longer moves.

I dream of my father’s drum. Of the river behind my home. Of firelight and songs. But these dreams are growing quiet.

The white man stands above us, writing something. He wears no uniform. He does not speak. Only watches.

I am afraid. I am resolved.

The archives may call us “cargo.” But my name is Adjoa.

Is this the end?

Or the beginning of something worse?

It has seen thousands leave.

It remembers their names, though no one else does.

It swallowed the screams.

It carried the chains.

And it waits, still.

Dutch records confirm that even after the legal ban of 1814, clandestine slave trading continued at Elmina, hidden in letters and ledgers now preserved in London’s archives > kb.nl.

There are no definitive records of the final shipments or their exact dates—only hints in shipping papers, captured correspondence, and defunct manifests.

Archival materials recount physical descriptions of enslaved individuals—“blind in one eye,” “lame arm,” “old and decrepit”—revealing the humanity behind the faceless suffering > kb.nl.

Some ships—like the fictional De Vlinder—sailed under false papers, smuggling enslaved Africans to Brazil, the Caribbean, and South America, even after abolition.

The names of those taken were never recorded.

But the castle still stands. And the sea still remembers.

A Dutch archive—Prize Papers in London—preserves just this: twisted piles of shipping letters from Elmina indicating clandestine trade persisted, even after abolition kb.nl. They care not about souls—only ledgers.